What have the Romans ever done for Nantwich?

The town of Nantwich has a long and interesting past. But how far back into the haze of history does it go? Visitors to Nantwich come to enjoy an afternoon exploring the shops and cafes, surrounded by ancient architecture, some even surviving the devastating fire of 1583, like the Elizabethan timber-framed Churches Mansion built just a few years prior in 1577. Or perhaps the magnificent St Mary’s Church, the construction of which began around 1340 – almost 700 years ago!

That’s a long time ago, sure, but written historical records go back ever further. The Domesday Book mentions Nantwich, or, using its description at the time ‘Wich in Warmundestrou’ in 1086. The entry is a surprisingly detailed account relating to the value and customs of the salt industry valuing it at the princely sum of £21 per year.

We can only imagine what Nantwich might have looked like over 900 years ago, never mind even longer ago than that. Traces remain though, hidden, underground, perhaps under your house or street, of the origins of Nantwich, some 1,900 years ago!

Time on this scale is often difficult for us to comprehend. To give you an idea, that’s 1,400 years before the Great Fire and 900-odd years before the Norman Conquest and the Domesday book. Right back to the time of the Romans and their Emperor Hadrian whose reign came to an end with his death in the year 138 AD.

Hadrian traveled the known world, even venturing to the territory to the far northern extremes of his empire, Britannia. He ordered the building of his famous wall across the island which still stands today, marking the end of his ‘civilized’ world and the start of the Barbarian wilderness. His travels no doubt made possible through the use of that most Roman of Roman things – The Road.

And this is where our story begins. A tiny outpost, next to the River Weaver and most importantly for the Romans – Salt.

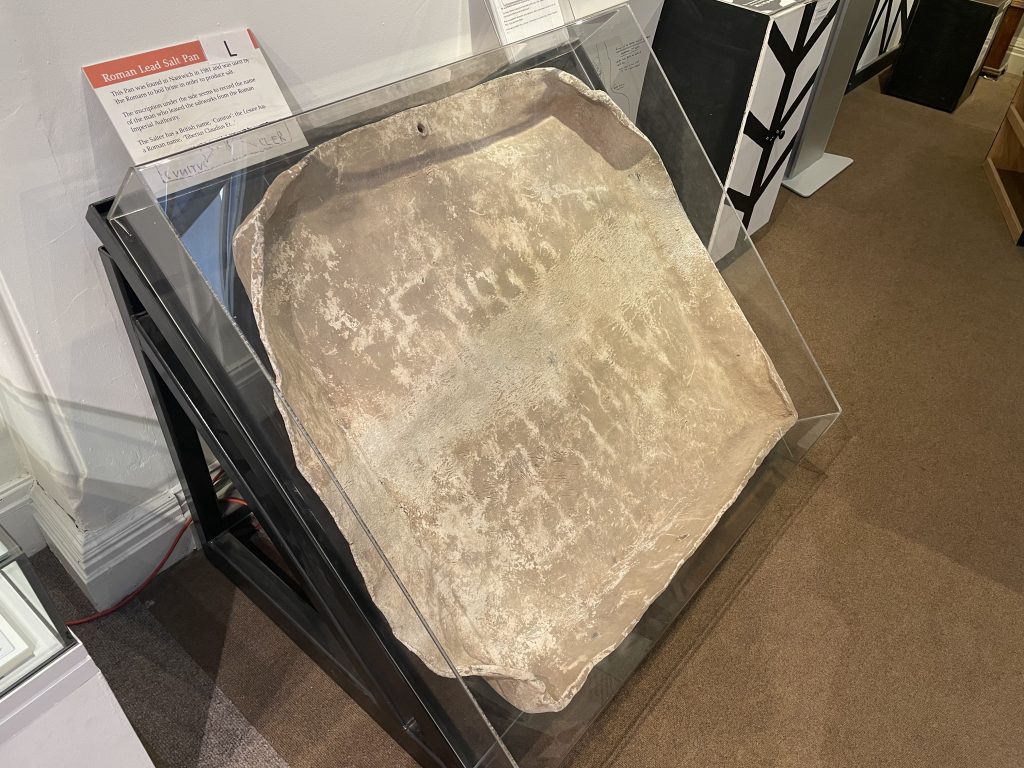

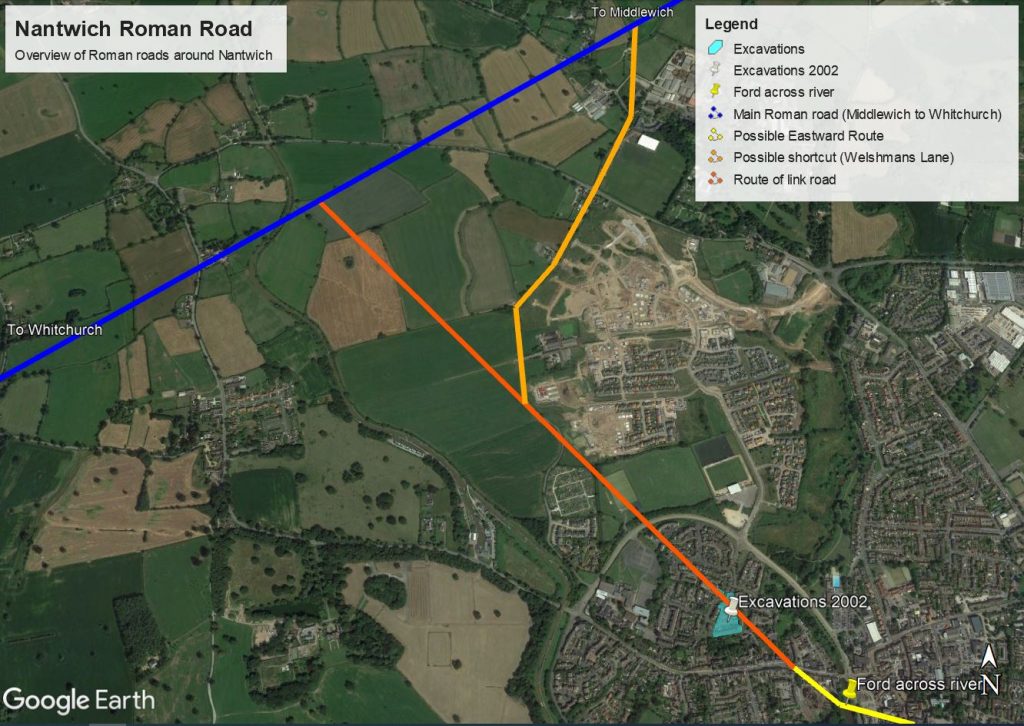

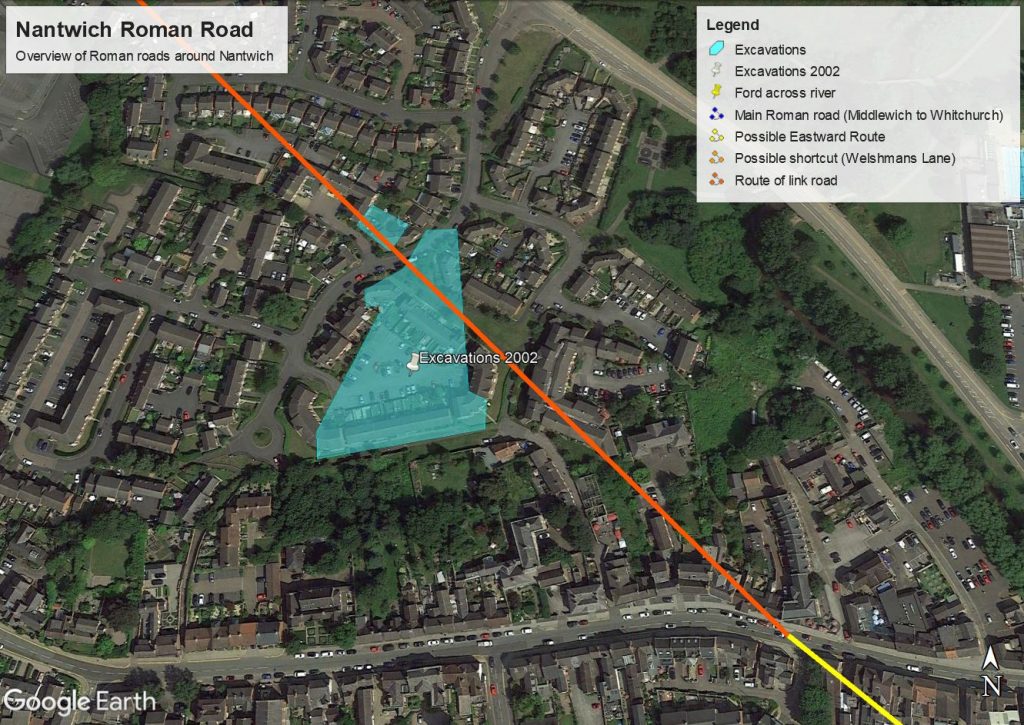

In the early 2000s excavations were dug to the North of Welsh Row in an area of farmland which was about to be developed into a new housing estate. Archaeologists knew that Nantwich’s origins were likely Roman. There was lots of evidence of Roman activity in similar towns like Middlewich, only 9 miles away, as well as Roman coins and pottery being uncovered in Nantwich itself during previous excavations. There had even been the discovery in 1981 of lead pans used in ancient salt production, possibly marked with the owner’s name ‘Cunitus’. It was a mystery then to consider why Nantwich was by-passed when Roman engineers built the road between Middlewich, or Salinae ( Meaning ‘The Salt Pans’ or ‘ The Salt Workings’) as they knew it and Whitchurch, less than One and a half miles away to the North West.

The blanks were filled in however when discovery was made of an ancient road running roughly SE to NW (Red on the map) in the North of the site linking Nantwich to the main Roman road (Blue on the map). Its rough path, strait of course in the Roman style, stretching from modern day Welsh Row probably somewhere between St Anne’s Lane and Red Lion Lane, through the modern housing estate, over the Waterlode bypass, through the Football pitch at Malbank School and for a short distance matching up with Welshmans Lane and finally across fields to meet the main road.

It has been suggested that Welshmans Lane (shown on the map in Orange) might have originally been a route to cut the corner between Nantwich and the main road towards Middlewich.

Alongside the road, the archaeologists found evidence which points to Nantwich being an important source of salt for the Roman army. It would have been a small settlement compared to the size of Nantwich today. In fact the evidence uncovered suggests that the road and structures found in the fields to the north of Welsh Row were probably the Northern and Western extremes, with a ditch found at St Anne’s lane in an earlier dig likely marking its southern boundary. To the East, just across the river some Roman pottery has been found along with some timbers and even a leather shoe however the Eastern extent of the settlement is still unclear. So Nantwich was small then, but the brine springs and the salt they produced meant that it was very important to the Romans nonetheless.

For most of the second century salt was produced for the Roman Army probably by slaves. It was used as a preservative and to season food as well as in leather making and the dyeing of fabrics. It’s often said that soldiers were sometimes paid in Salt (or at least given a monthly ration or Salarium) or Sal in Latin, eventually morphing into modern use as the word Salary. Salt also has antiseptic qualities, the Roman Goddess of Health was called Salus

The waterlogged ground around this area is a pretty good environment for the preservation of wood, leather, metal and pottery leading to much more being found besides the road. The site produced 355 timbers, various pieces of leather, 164 brick and tile fragments, 18 wooden objects including salt making tools and what may be a musical instrument, as well as 52 coins and 3919 pottery sherds.To the South of the site, two large tanks were uncovered, dug into the ground and lined with a wooden frame and clay to provide a waterproof layer, designed to store the brine from the spring. To give an indication of scale, these tanks could hold brine which once evaporated could produce 23 tonnes of salt!

Between the brine tanks and the road, archaeologists uncovered the remains of two large buildings contained within an enclosure, probably connected with the salt works. Next to this, evidence of hearths which could have been used for the fires needed to evaporate the water from the brine, leaving behind the valuable salt crystals. This industrial complex may extend further South into the area now making up houses along the North side of Welsh Row.

So the link road was built to connect the Nantwich salt industry to the rest of Roman Britain and it grew and prospered until 1900 years later and became Nantwich as we know it today.

Well, not quite.

Time passed and needs changed. In the later part of the 2nd century and into the 3rd the evidence shows a downturn in salt production and a decline in the use of the site. The two large tanks dug into the ground are now out of use and have become a ‘watery place’ for making offerings. People carefully placed valuable pottery and tools as well as animal remains into the pits for ritual purposes. The road remains, although narrowed.

Some time in the first half of the 3rd century the site came back to life. The buildings were gone but the enclosure remained. The large wood-lined brine tanks were not brought back into use however but continued to be a place for ritual offerings. A new building is present along with an enclosure and new small wood-lined pits are used for the collection of brine.

This revival came to an end not long after with the middle of the 3rd century marking the start of a period of smaller scale production using wicker lined pits with short working lives. Eventually salt production on this site ends, perhaps moving to another location or stopping all together. Archaeologists suggest that this might echo a wider decline in the area’s industries which wouldn’t reverse until after the Romans. Nantwich, or what remained of it, may have become a more agricultural settlement for a while. What is known though, is that our road was still in use for many, many more years to come.

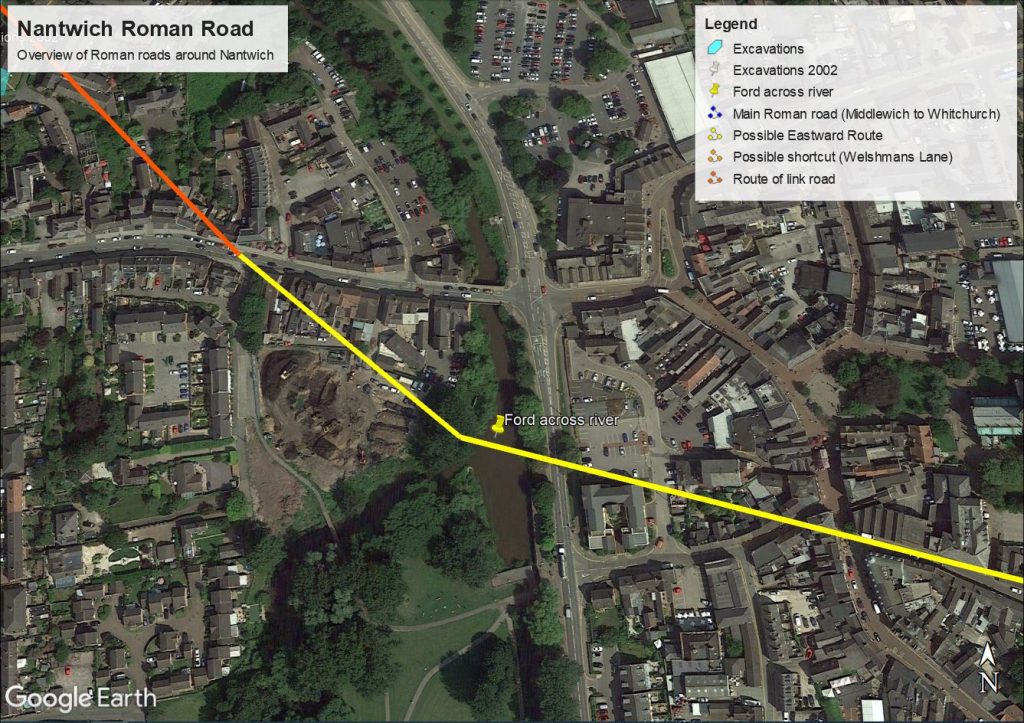

Shards of pottery found in the ditches running alongside the road suggest use into late medieval times. More evidence was uncovered on Welsh Row where a probable continuation of the road was found 2.5 meters below the modern road. The Roman surface was covered by a later layer which could be dated to some time in the early 11th to mid 12th century. Further evidence to the East showed that Welsh Row existed by the second half of the 13th century meaning that it eventually replaced the Roman road more than 1,000 years after its construction.

Researchers at Nantwich Museum have concluded that it is likely that the road continued in a similar direction South Easterly across what we know now as The Gas Works (soon to be redeveloped) to meet the river and a ford crossing to the North of Mill Island, giving access to the East side of the settlement, which was perhaps mainly residential in nature. From here the route of the road is unclear. The researchers think that the most likely route is out of town to the East forming what is now Hospital Street (Yellow on the map).

The road and surrounding land with its long history of journeys begun and ended, worn cobble stones and generations of sweat and toil were turned into farmland and so it remained until 2002 when it was rediscovered, measured, analyzed, documented, covered over and added to the history books.

Perhaps you live above the Roman Road or the brine pits or the offerings to the gods? What a thought!

REFERENCES

P Arrowsmith & D Power (2012) Roman Nantwich – A Saltmaking Settlement (BAR 557). Archaeorpess

B Strawson (2021) Roman Nantwich – Nantwich Museum.

B Stawson (2022) The Making of Nantwich in Six Maps – Nantwich Museum